8 minute read. Content warning: Nudity (discussion and process video – age restricted login on youtube required), detailed body description, including imperfections, scars, and body hair, and mentions of societal perceptions of nudity and body image.

chatGPT Summary: A reflective exploration of the process and concepts behind “The Unseen,” an artwork series where Kay grapples with body representation, the nuances of visual description, and the challenges of working within physical and societal constraints.

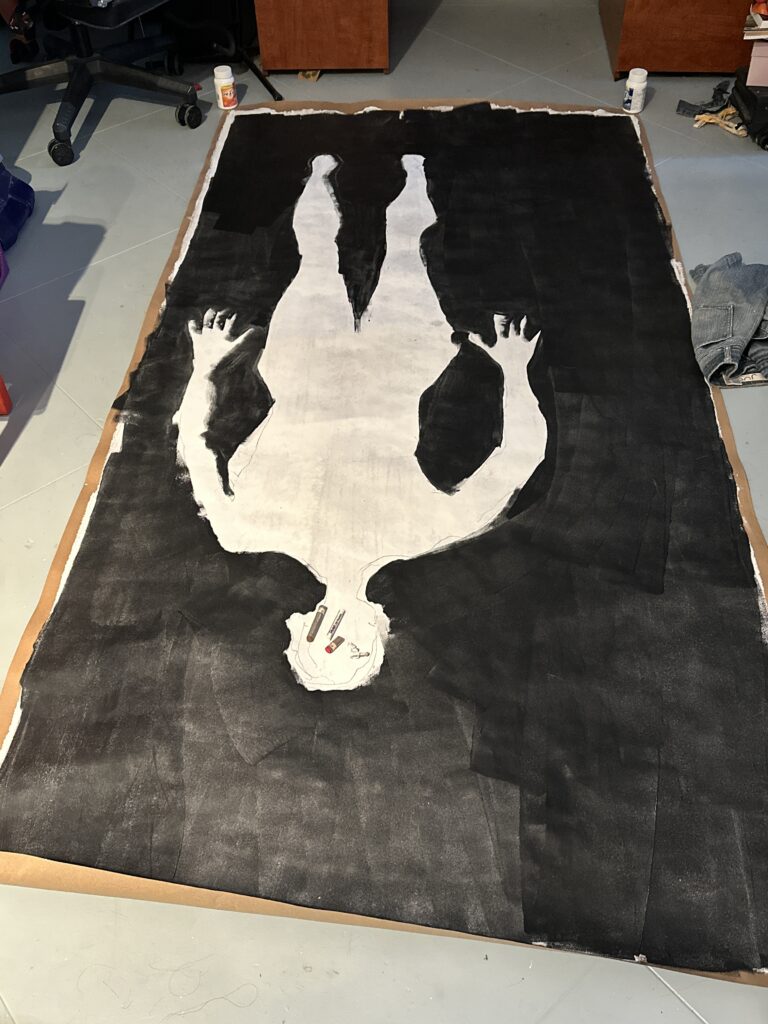

Process notes for the (first) longest piece:

A prototype performance:

I decided to approach the first piece like a performance. If this process were being verbally described to a non-visual audience while being observed by a live visual audience, how would they perceive it?

I think initially, it would be really easy to dismiss this as juvenile, especially in my own experience within the Western public school system; tracing one’s outline is not particularly complex. However, I did this solo, requiring more physicality than I had expected. I had traced my hand before but never my own body—not that I remembered. I had a few things in mind, having done this both as the tracer of another body and having been traced, but I certainly wasn’t an expert in full-body tracing and was excited to see what would happen.

I knew I would have to commit either to a tight line around my body, pushing against the fat and muscle, or I would need to employ a soft hand to get the more subtle variations of my body. My breasts, my thighs, any place where there would be the impulse to push in and get resistance. This, in turn, made me think it would be best to be naked, not even a blip of an issue in my studio, but in the context of a public performance, it would be more complicated. Nudity carries a lot of subjective weight, and sadly, Western English and North American society still shames or assigns titillation to any non-cis-male body on display. For myself, being naked is not a big deal, and in my life, I have been told that I should feel more shame and that it isn’t about me, but rather for the sake of others that clothing is necessary and is a sign of respect. I am also a non-binary body with a set of very obvious breasts. Exposing these in a performance would have consequences. However, if I wanted various elements of my body to be traced on the page, covering them, contained for the sake of modesty, I would be choosing the comfort of my audience over my drawing. I decided to split the difference, going topless but remaining covered on my bottom and recording the initial tracing.

The drawing:

I had forgotten that by tracing in a bird’s eye view of my prone position, I would need to either unnaturally position my feet to the side so that they could appear on the page and that the position of my hands would dictate whether or not I would have articulated fingers or not. I leaned down to trace the heel of my foot, deciding not to trace an unnatural foot position for the sake of including a recognizable shape – a tactic used by grade school children. I watched how sitting up caused my heel to move down and my legs to lengthen, and I had to adjust, shifting my bottom back to a similar position so that my feet touched in the same place as they would when I was lying down. This real-time solving of problems was exciting, and I was encountering things I wouldn’t have if I had had an assistant.

I also quite enjoyed the fact that my lines were imperfect. Sometimes, the pencil would follow the fat and skin of my body, but other times, it would shift into an angle to fall past the edge and down around my body’s curve towards the page. As I drew, I realized I would not get a faithful representation, which freed me from worrying about accuracy and allowed me to be very present and focused as I marked different areas of my body.

After filming the process of my first piece, I have become more convinced that this series would benefit from a performance element, both to provide more opportunities for live descriptions of drawing, the process of overcoming drawing challenges in real-time, and contemporary art performance, but also to, be able to compare the reactions of a live audience who would make assumptions based on what they saw, observed, or had narrated to them in real-time, compared to those who would see the finished work and be presented with information that allowed them to consider the seen, described, and unseen. A performance and a leave-behind drawing would allow for two concurrent narratives to develop.

When I stood up and observed the strange and shaky outline of my contour, I noticed that I had successfully captured the outline of my prone and flattened breast on one side and had erased it on the other by digging in deep and running the underside of my rib cage.

The painting:

I grabbed my black paint to fill the space around the drawing. I introduced another element of imperfect drawing by using a flat roller, which allowed for quick pigment application and forced me to contend with more unpredictable, organic lines. Filling in the negative space around the contour sometimes erased or corrected spaces that the contour drawing had not captured.

The result is messy, dynamic, and doll-like.

It is my body, yet devoid of unique characteristics, it could be anybody’s. In this first performance attempt, I am more convinced that the gesso and black media are the right way to go, but I will push back against that stubborn thought and eventually try with non-gesso surfaces or different colours. The black feels right, creating a high contrast background compared to the messy white silhouette, and if I do it on brown kraft paper, the body silhouette becomes charged and may take up a space I don’t intend to. However, it also introduces a conversation around race and blindness – something I can’t talk to directly but could be a conversation hosted concurrently with this content. I can acknowledge that some non-visual audiences might not care about the colour surrounding or filling the body, but just because the information is not relevant or important to one participant doesn’t mean I should ignore the chance to host the conversation.

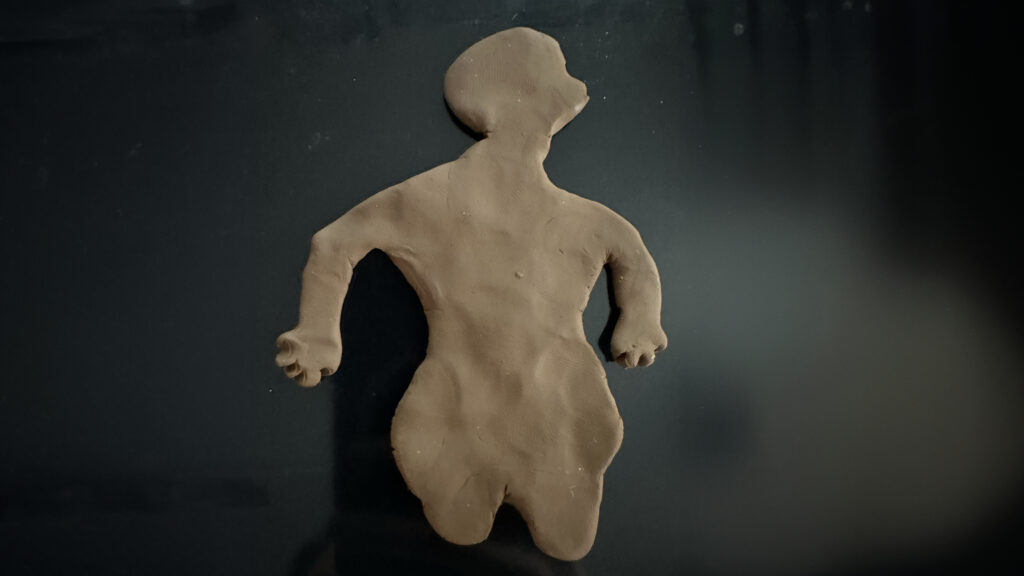

As I let the paint dry, I asked myself how to introduce the tactile element to this work. Before I add any text description, this work will rely heavily on someone describing what they see. Perhaps an equivalent would be to re-create these imperfect body forms as actual dolls so that each iteration that becomes cropped could be felt and so that both non-visual and tactile-experience audiences would be required to rely on filling in the blanks with the additional written text information I provide. Perhaps in a performance context, I could mold a quick plastercine equivilent while the paint dried?

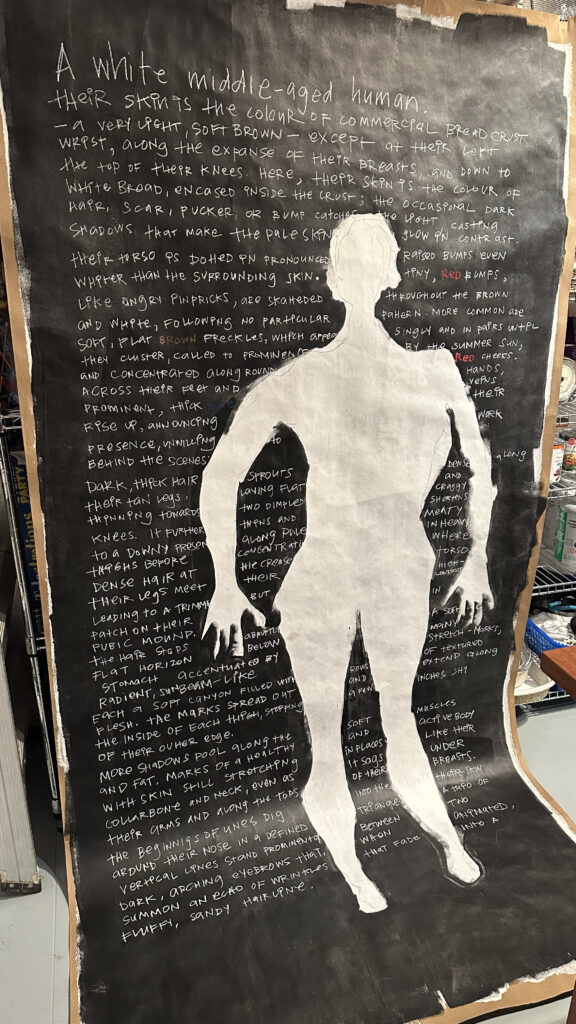

The writing:

I wanted to ensure that I wrote enough in the earlier works so that the text would fill most of the space around the silhouette. I would start by focusing on larger, more abstract things with a full, uncropped body form, and then as I dealt with a smaller space and smaller body parts, I would need to work harder to be more effective and efficient with fewer words.

Yet, after an hour on my knees on my hard concrete floor, moving across a 4-foot expanse of paper, I am exhausted. I decided that any colours mentioned, besides my skin tone, would be written in coloured oil pastel, and otherwise, the text would be a white conté, less prone to smudging with a good contrast against black paint. These ideas were sound, but holding the conté in such a way that my marks were pronounced while still maintaining my handwriting gesture (I didn’t want to change my writing style), I dealt with a lot of body pain. While the drawing and painting felt performative and interesting, I filmed the writing and cut it into a shorter time-lapse. The writing process, while essential, lacks dynamism—it’s simply a description of my body

I have now completed 1/31 works, and while my enthusiasm has dulled from the physical intensity required for the writing, I do remain excited about completing this project. While my body is the subject, prompted by KM’s question about the pieces of ourselves, I like the concepts and conversations I have started by this practice. Even though I am looking across the chasm of hours of labour only to produce an early prototype – I still want to get to the end. I’ll not be able to complete this before the end of August; the materials are too cumbersome to take with me on my residency later this month and require space and time within a shared living and working space with my partner. Still, I should have enough assembled for our collective’s end-of-summer meet-up, where we share the ideas that shook out from our prompt-based, distanced collaboration. This idea will also benefit from outside perspectives and feedback.

The text reads:

A white, middle-aged human. Their skin is the colour of commercial bread crust—a very light, soft brown—except at their left wrist, along the expanse of their breasts, and down to the tops of their knees. Here, their skin is the colour of white bread, encased by the light crust; the occasional dark hair, scar, pucker, or bump catches the light, casting shadows that make the pale skin glow in contrast. Their torso is dotted with pronounced, raised bumps even whiter than the surrounding skin. Tiny, red bumps, like angry pinpricks, are scattered throughout the brown and white, following no particular pattern. More common are soft, flat, dark brown freckles, which appear singly and in pairs until they cluster, called to prominence by the summer sun and concentrated along round red cheeks. Across their feet and hands, prominent, thick blue veins rise up, announcing their presence, unwilling to work behind the scenes alongside these active appendages.

Dark, thick hair sprouts densely along their tan legs, laying flat and thinning toward two dimpled and craggy knees. It further thins and shortens to a downy presence along pale, meaty thighs before concentrating in heavy, dense hair at the crease where their legs meet their torso, culminating in a trimmed but high-contrast patch on their pubic mound. The dark hair stops abruptly in a flat horizon below a soft stomach, lined with many concentric sunbeams of stretch marks, each a soft depression filled with perpendicular rows of textured flesh. The marks spread out and extend along the inside of each thigh, stopping a few inches shy of their outer edge.

More shadows pool along the soft muscles and fat, marks of a healthy and active body, with skin still stretching in places like the collarbone and neck, even as it sags under their arms and along the tops of their breasts. The beginnings of lines dig into the skin around their mouth, leading up to their nose in a defined triangle. A trio of vertical lines stand prominently between two dark, arching eyebrows that, when animated, summon an echo of wrinkles that fade into a fluffy, sandy hairline.

Technology note:

I continue to test the use of AI within my writing and artistic practice. I used chatGPT to create a summary, recommend content warnings, and provide a reading time estimate for this blog, and Grammarly to assist me in spelling and grammar.

I used a DJI gimbal to hold my camera and film my process, and iMovie to timelapse and edit.